http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5913a3.htm?s_cid=mm5913a3_e

Weekly

April 9, 2010 / 59(13);393-396On October 19, 2009, clinicians from Kentucky contacted CDC regarding a suspected case of rabies in a man from Indiana aged 43 years. This report summarizes the patient's clinical presentation and course, the subsequent epidemiologic investigation, and, for the first time, provides infection control recommendations for personnel performing autopsies on decedents with confirmed or suspected rabies infection. Before the patient's death on October 20, a diagnosis of rabies was suspected based on the history of acute, progressive encephalitis with unknown etiology. Preliminary serology results on antemortem serum samples detected rabies virus-specific antibodies. Because local pathologists were concerned about the biosafety risk posed by infectious aerosols at autopsy and potential contamination of autopsy facilities, the Kentucky Department for Public Health (KDPH) asked CDC staff members to travel to Kentucky and perform an autopsy to confirm the diagnosis and assist with the epidemiologic investigation. Testing of autopsy samples was conducted at CDC and detected rabies virus antigens in brainstem and cerebellum. Rabies viral RNA was isolated and typed as a variant common to the tricolored bat (Perimyotis subflavus). Although rabies virus transmission from organ or tissue transplant has been documented rarely (1,2), transmission of rabies virus to persons performing autopsies has not been reported. Autopsies can be performed safely on decedents with confirmed or suspected rabies using careful dissection techniques, personal protective equipment, and other recommended precautions.

Case Report

On October 5, 2009, a previously healthy man from Indiana aged 43 years visited an employee health clinic with fever and cough. His vital signs and physical examination were unremarkable except for coarse rales on lung auscultation. The clinician made a diagnosis of bronchitis, prescribed antibiotics, and asked the patient to return the following day. At this follow-up appointment, the patient reported worsening fever and chills, as well as new chest pain and left arm numbness; he also exhibited decreased grip strength of the left hand. An electrocardiogram showed no evidence of cardiac ischemia. Later that day, an evaluation at a local emergency department was similarly unrevealing, and the patient was given narcotics and muscle relaxants for presumed musculoskeletal pain and discharged home.

On October 7, the patient returned to the same ED, where he was noted to have akathisia and motor restlessness thought to be side effects from the muscle relaxant. The ED physician advised admission to the hospital, but the patient returned home. Upon follow-up the next day with a primary-care physician, the patient had prominent muscle fasciculations, fever, tachycardia, and hypotension. Given these signs, the physician was concerned about the possibility of sepsis and admitted him to the hospital.

After admission, the patient's mental status deteriorated rapidly, and he underwent endotracheal intubation for airway protection. On October 9, he was transferred to a referral hospital in the neighboring state of Kentucky. A lumbar puncture yielded cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with glucose of 72 mg/dL (normal: 40--70 mg/dL), protein 140 mg/dL (normal: 15--45 mg/dL), 3 red blood cells/mm3 (normal: 0--2 cells/mm3), and 38 white blood cells /mm3 (normal: 0--5 cells/mm3); differential showed 99% lymphocytes and 1% monocytes. During October 9--19, no etiology for the patient's disease was identified, and his hospital course became complicated by bradycardia, hypotension, rhabdomyolysis, and renal failure requiring hemodialysis. Results of a magnetic resonance image of the brain and a brain perfusion study were normal. Bacterial and fungal cultures of CSF, in addition to laboratory tests for West Nile virus, herpes simplex virus, influenza, and human immunodeficiency virus, were negative.

On October 19, diagnostic testing for rabies was requested, and samples of the patient's serum, saliva, and a nuchal skin biopsy were sent to CDC for analysis. However, on October 20, while these tests were pending, the patient's physical examination, electroencephalogram, and apnea testing all indicated brain death. Ventilatory support was withdrawn, and the patient died on October 20.

Postmortem Findings

On October 22, testing at CDC indicated rabies specific immunoglobulin G (1:2,048) and immunoglobulin M (1:512) antibodies in serum by the indirect fluorescent-antibody (IFA) assay. Subsequent testing detected rabies virus neutralizing antibodies (0.44 IU/mL) in serum by rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test (RFFIT). The formalin-fixed nuchal skin biopsy specimen tested negative for viral antigens by immunohistochemistry (IHC). On October 27, a CSF sample collected on October 11 and located postmortem was sent to CDC and also tested negative for rabies antibodies by IFA and RFFIT. The family requested an autopsy, but pathologists at the referral hospital were concerned about the biosafety risk posed by infectious aerosols at autopsy and potential contamination of autopsy facilities. Attempts to identify other personnel and facilities willing to perform the autopsy, including several tertiary-care and teaching centers in Kentucky, Indiana, and Tennessee, were unsuccessful because of similar concerns. In response to a request for assistance from KDPH, CDC staff members traveled to Kentucky and performed an autopsy limited to the head to collect tissue specimens for diagnostic evaluation.

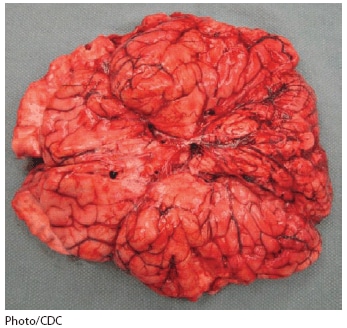

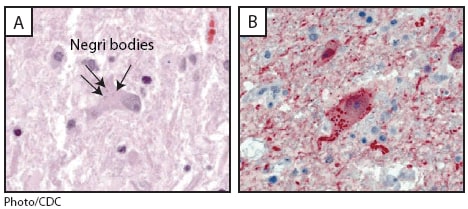

At autopsy, the brain weighed 1,610 g (normal: 1,300--1,400 g) and showed markedly congested and hemorrhagic leptomeninges (Figure 1). Histopathologic examination revealed encephalomyelitis and abundant neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions (Negri bodies) (Figure 2). Rabies virus antigens were detected in multiple samples of fresh central nervous system (CNS) tissue by direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) testing and in formalin-fixed CNS tissues by IHC (Figure 2). Viral RNA was detected in the patient's saliva collected antemortem and CNS tissues collected at autopsy by reverse transcription--polymerase chain reaction and was typed as a variant common to the tricolored bat (Perimyotis subflavus).

Public Health Investigation

The referral hospital and CDC notified KDPH and the Indiana State Department of Health (ISDH) about the case on October 21, the day before rabies virus-specific antibodies were found in the patient's serum. Beginning on October 23, ISDH, with the assistance of the local health department and, later, CDC, began interviewing the patient's close contacts, including family, friends, coworkers, and health-care personnel, to clarify his exposure history and determine whether rabies postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) should be recommended to any of the contacts. The investigation identified no specific source of rabies virus exposure. However, the patient, who worked as a mechanic and lived in a farming community in southern Indiana, had mentioned to his friends that he had seen a bat in late July after removing a tarpaulin from a tractor adjacent to his residence. He had not mentioned a bite or a nonbite exposure associated with this or any other incident.

The investigation identified 159 persons who had interaction with the patient 2 weeks before or during the 2-week duration of his illness. All of these 159 persons were counseled about the potential risks associated with rabies virus exposure. Investigators distributed a handout detailing basic information about rabies, how the virus is transmitted, and what constitutes an exposure. Of the 159 persons, 147 were health-care providers who treated the patient during his visits to four medical facilities, or who transported him between hospitals. Two family members, two coworkers, and 14 health-care providers were identified as having been potentially exposed to saliva from the patient. All 18 were recommended to receive rabies PEP, and all completed the vaccination series according to Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommendations (3,4). To date, none of the 159 persons has developed rabies.

Reported by

J House, DVM, Indiana State Dept of Health; J Poe, DVM, K Humbaugh, MD, Kentucky Dept for Public Health; C Drew, DVM, PhD, C Paddock, MD, S Zaki, MD, PhD, C Rupprecht, VMD, PhD, Div of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Diseases; M Ritchey, DPT, B Petersen, MD, EIS officers, CDC.

Editorial Note

The case described in this report represents the first rabies death in an Indiana resident since 2006 and only the second such death since 1959. Including this case, a total of 31 cases of human rabies have been reported in the United States since 2000. Of these, 14 (45%) were diagnosed postmortem, reinforcing the need to consider rabies in all cases of acute progressive encephalitis of unknown etiology. Human rabies cases in the United States might be underreported because of lack of recognition and lack of confirmation by diagnostic testing. When rabies is suspected, antemortem diagnosis requires testing of serum, saliva, CSF, and a nuchal skin biopsy.

The postmortem diagnosis of rabies is made by examination of tissue from the brain (e.g., medulla, cerebellum, and hippocampus). Autopsies fulfill an important function by diagnosing cases of rabies and furthering understanding of the disease. By providing a diagnosis for deceased patients with suspected but unconfirmed rabies, or for patients in whom the disease was never suspected clinically, autopsies can 1) aid the public health investigation, 2) help raise public awareness of rabies associated with specific exposures, 3) emphasize the importance of seeking medical evaluation after such an exposure occurs, and 4) add to knowledge about current human rabies incidence. In patients with confirmed rabies, autopsies provide information about pathogenesis that might be relevant to investigations of treatment.

Although contact with decedents with confirmed or suspected rabies can cause anxiety, no confirmed case of rabies has ever been reported among persons performing postmortem examinations of humans or animals. Even from living patients with rabies, human-to-human transmission has been documented only rarely, in cases of organ or tissue transplantation (1,2). Aerosol transmission of rabies virus has never been well documented outside of a research laboratory setting (5). Both CDC and the World Health Organization (WHO) have stated that the infection risk to health-care personnel from human rabies patients is no greater than from patients with other viral or bacterial infections. In addition, rabies PEP is available for exposed personnel. Nevertheless, because of the nearly universal fatal outcome from rabies, both CDC and WHO recommend that all personnel working with rabies patients or decedents adhere to recommended precautions (3,6).

Even the minimal risk for rabies virus transmission at autopsy can be reduced by using careful dissection techniques and appropriate personal protective equipment, including an N95 or higher respirator, full face shield, goggles, gloves, complete body coverage by protective wear, and heavy or chain mail gloves to help prevent cuts or sticks from sharp instruments or bone fragments (Box). Aerosols should be minimized by using a handsaw rather than an oscillating saw, and by avoiding contact of the saw blade with brain tissue while removing the calvarium. Ample use of a 10% solution of sodium hypochlorite for disinfection is recommended both during and after the procedure to ensure decontamination of all exposed surfaces and equipment. Participation in the autopsy should be limited to persons directly involved in the procedure and collection of specimens. Previous vaccination against rabies is not required for persons performing such autopsies. PEP of autopsy personnel is recommended only if contamination of a wound or mucous membrane with patient saliva or other potentially infectious material (e.g., neural tissue) occurs during the procedure (3,7,8). The case described in this report highlights the need to educate pathologists and other hospital personnel about appropriate rabies infection control procedures so that autopsies can be performed safely in cases of confirmed or suspected human rabies.

Acknowledgments

This report is based, in part, on contributions by staff members of the Clark County Health Dept, Jeffersonville, Indiana; staff members of the Louisville Metro Dept of Public Health and Wellness, Louisville, Kentucky; C Biehle, Saint Catherine Regional Hospital, Charlestown, Indiana; M Nowacki, MD, A Razzino, MSN, MBA, Norton Hospital, Louisville, Kentucky; P Pontones, MA, J Howell, DVM, J Ignaut, MA, MPH, Indiana State Dept of Health; and A Velasco, PhD, M Niezgoda, MS, L Orciari, MS, and P Yager, Div of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Diseases, CDC.

References

What is already known on this topic?

If not prevented by administration of postexposure prophylaxis, the rabies virus causes an acute progressive viral encephalitis that is almost always fatal.

What is added by this report?

In October 2009, a man from Indiana aged 43 years died of rabies; the diagnosis was made postmortem and confirmed by samples collected at autopsy.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Recognizing and diagnosing human rabies is critical in initiating an appropriate clinical and public health response, furthering understanding of the disease, and implementing appropriate prevention and control measures; autopsies can be performed safely on decedents with confirmed or suspected rabies using careful dissection techniques, personal protective equipment, and other recommended precautions.

Alternate Text: The figure above shows a brain at autopsy of a decedent with suspected rabies infection in Indiana during 2009. At autopsy, the brain weighed 1,610 g (normal: 1,300-1,400 g) and showed markedly congested and hemorrhagic leptomeninges.

FIGURE 2. Histopathologic examination of central nervous system tissue from autopsy of a decedent with suspected rabies infection, showing neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions (Negri bodies) after hematoxylin and eosin staining (panel A) and rabies virus antigen (red) after immunohistochemical staining (panel B) --- Kentucky/Indiana, 2009

Alternate Text: The figure above shows photos from a histopathologic examination of central nervous system tissue from the autopsy of a decedent with suspected rabies infection in Indiana during 2009, showing neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions (Negri bodies) after hematoxylin and eosin staining and rabies virus antigen after immunohistochemical staining.

• Use personal protective equipment, including an N95 or higher respirator, full face shield, goggles, and gloves, as well as complete body coverage with protective wear. • Use heavy or chain mail gloves to help prevent cuts or sticks from cutting instruments or bone fragments. • Minimize aerosol generation by using a handsaw rather than an oscillating saw and avoiding contact of the saw blade with brain tissue while removing the calvarium. • Limit participation to those directly involved in the procedure and collection of specimens. • Use ample amounts of a 10% sodium hypochlorite solution during and after the procedure to ensure decontamination of all exposed surfaces and equipment • Previous vaccination against rabies is not required for persons performing such autopsies, and postexposure prophylaxis of autopsy personnel is recommended only if contamination of a wound or mucous membrane with patient saliva or other potentially infectious material (e.g., neural tissue) occurs during the procedure. |

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are provided as a service to MMWR readers and do not constitute or imply endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed in MMWR were current as of the date of publication. |

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

**Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário